Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) is a common anxiety disorder which is thought to affect approximately 2 in 100 people in the population.

- An obsession is an unwanted and unpleasant thought, image or urge that repeatedly enters your mind, causing feelings of anxiety, disgust or unease.

- A compulsion is a repetitive behaviour or mental act that you feel you need to carry out to try to temporarily relieve the unpleasant feelings brought on by the obsessive thought.

Many people experience thoughts that they don’t like or don’t understand from time to time. For example, when holding a small animal you might have an image or thought about holding it too tight injuring it, you might think about what would happen if you drove onto the wrong side of the road or said something inappropriate in an important meeting. These thoughts don’t normally mean you actually want to embarrass or hurt yourself and the thoughts normally go away on their own.

If you have OCD these thoughts cause lots of anxiety and they can be extremely difficult to ignore. You might find that you spend lots of time worrying about what your thoughts mean. You might also complete behaviours to try and stop your feelings of anxiety.

Not everyone who experiences obsessions will have compulsive behaviours but often compulsive behaviours are very subtle and feel like a natural reaction to obsessive thoughts. You might perform a behaviour that seems unrelated to your original worry, for example repeating a certain word or phrase to yourself to “neutralise” a thought.

Superstitious thinking

Often people with OCD can feel that thinking about certain things makes them more likely to happen. For example, you might worry that you shouldn’t think about an accident happening in case you feel responsible for it. This is called superstitions or magical thinking.

Imagine you were asked to think about someone you love and complete the sentence below by entering their name and then signing and dating it.

You would likely be very unhappy doing this and might refuse to do the task altogether. You might feel that you are “tempting fate” and would feel a terrible sense of responsibility if something happened to your loved one.

But does writing something on a piece of paper make it more likely to happen? What if you were asked to fill in this sentence?

Would you be able to claim part of the prize money if they won? Could you take them to court and demand money back? You would likely find it easier to fill in the second example than the first but the truth is you can’t control the world with your thoughts.

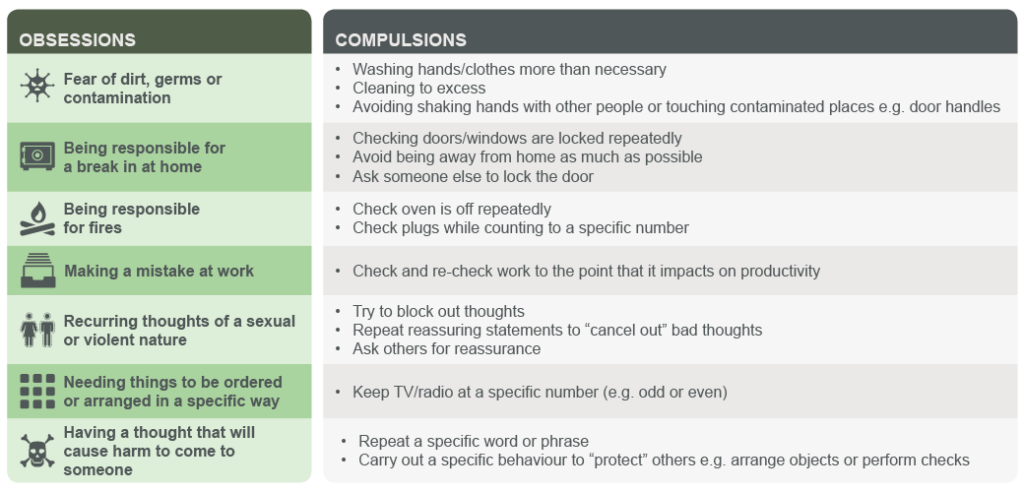

Below is a table of some common obsessions and compulsions:

Below are some links to questionnaires which assess whether you might have obsessive compulsive disorder

OCD Self-Assessment – Anxieties.com

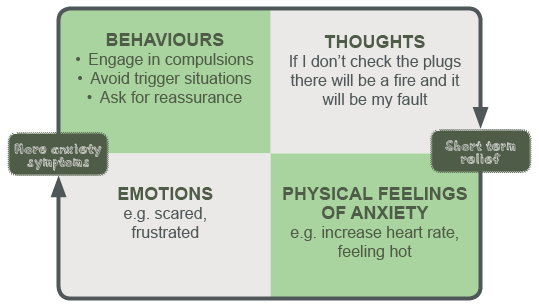

This diagram shows how your thoughts and feelings can lead to unhelpful behaviours and how these behaviours then make the thoughts worse.

Hoarding- although it is not always related to OCD, some people also have difficulties with hoarding. You might be having difficulties with hoarding if you find it very difficult to throw things away and end up with lots of things stored in a very chaotic way.

More Information

What helps

The two most evidenced treatments currently for OCD are:

- Medication – usually a type of antidepressant medication that can help by altering the balance of chemicals in your brain.

- Talking therapy – usually a type of therapy called Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (or CBT) which helps you to change your thoughts, feelings and behaviours

Although lots of people benefit from psychological therapy alone, others combine medication and psychological therapy or only take medication.

If you are concerned that you may have OCD it is a good idea to meet with your GP who can guide you towards helpful services in your area.

Further information on treatment options for OCD is available at NHS Choices

There are a number of useful books and self-help materials available to help if you have OCD some of which are listed below:

Books

Break Free from OCD: Overcoming Obsessive Compulsive Disorder with CBT (2011) by Dr Fiona Callacombe and Dr Victoria Bream Oldfield

Overcoming Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: A self-help guide using Cognitive Behavioural Techniques (2009) by David Veale and Rob Wilson

Or

Stop Obsessing! How to Overcome your Obsessions and Compulsions (1991) by Edna B. Foa and Reid Wilson

There is growing popularity and the beginning of evidence to support another approach using mindfulness techniques. This can be used to complement other treatment approaches and is described in:

Mindfulness Workbook for OCD: A guide to overcoming obsessions and compulsions using mindfulness and cognitive behavioural therapy (2014) by Jon Hershfield and Tom Corboy

These are available to purchase on the internet and in bookshops.A good local library should also be able to lend you these books.

Websites

There are also very useful resources on the web which you can access:

What would a self-help programme involve?

If you choose to follow a psychological self-help programme, instead of, or alongside medication, here is an idea of the kind of approach you can expect.

You may be asked to think about how, when and why your difficulties started

For example,

- Can you remember when they first started?

- Were they a problem early on or did they only become a problem after a while?

- Can you think what might have led to you developing a problem with obsessions and/or compulsions?

- Did something happen around the time when you started to notice that they were becoming a problem? (this is sometimes called a ‘trigger’)

- Why do you think they have not got better by themselves?

You may be interested to know that…

- Some people with OCD have family members who have also had obsessions and/or compulsions- this could point to a genetic element, or it could be that it suggests we learn behaviours from those around us

- Sometimes the problem becomes more noticeable at times of change, for example when leaving home or having a first child

- Some people with OCD have an exaggerated sense of personal responsibility. For instance, they believe that if something bad happens they will personally be completely to blame for it, rather than there being many causes to most events.

- Some people who have checking compulsions believe that they have a poor memory, and therefore need to check their actions many times over. In fact, there is no evidence that people with OCD have poorer memories than anyone else. However, they do often have less confidence in their memory, for example having a recurring thought or belief that ‘My memory can’t be trusted’. You may want to reflect on how to build confidence in your memory, and we will look at this further in a later section.

Take a moment to reflect on how the above may apply to you

My understanding of how my OCD Developed

1……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

2…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

3……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

4……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

It is not necessary to find a cause for your OCD in order to change, but sometimes it can be helpful to think about how it has developed.

You may be asked to think about what is keeping your OCD going.

‘In CBT we believe that OCD continues because the strategies you may be using to try to tackle it are actually having the opposite effect’

If you check or repeat a ritual after an obsessive thought or image, you experience immediate relief from the distress or anxiety which the thought or image has caused. This can make you believe that your checking or ritual is working. So you want to keep using that method of making your anxiety go away. The problem with this strategy is that the relief from the anxiety does not last long. As soon as the obsession returns, the checking or ritual has to begin again. So not only the obsessions but also the compulsions and rituals become part of the problem.

Therefore the answer has to lie in finding a different response to the original distressing thought or image.

Take the example of a mother who lies awake at night, constantly with the image that she may inadvertently harm her children. She has never harmed anyone in her life and takes good care of her children who mean the world to her. This thought is completely out of character, yet she fears that it means something bad could happen to her children, or even that she could be responsible for it. Her strategy to cope with this is to make sure she stays awake to block out the thoughts and images, or she focuses on a spot on the ceiling to take her mind off her obsessions.

This might seem like common sense – of course, a mother would want to put any thoughts of her children coming to harm out of her mind. However what we know is that if we put a lot of effort into trying to block out thoughts, unfortunately, this can have the opposite effect.

Try this experiment:

Firstly, bring to mind a large pink caterpillar. Now I would like you to try very hard not to think of one.

What happened? Most people find that they can’t get the picture out of their head of a large pink caterpillar.

You can try this experiment with any intrusive thoughts or obsession that you may have. On Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday, try your hardest not to think about them. On Thursday, Friday and Saturday put less effort into not thinking about them. See what happens on each day. Does trying not to think about them make them less frequent or less distressing? Or more so?

Another important point is that most people experience upsetting thoughts at some point, such as the mother described above. These can include thoughts about harming others, behaving in a sexually or morally reproachable way, becoming critically ill, catching germs, leaving a door unlocked, or the gas turned on. The difference is that most people are able to dismiss these thoughts quickly, they do not dwell on them, neither do they put enormous energy into pushing them away or ‘neutralising’ them. They do not consider that these thoughts mean anything about them as a person, about other people, or about their environment as a potentially dangerous place.

Accepting thoughts as ‘just thoughts’ is key to overcoming OCD. If you can accept your thoughts and let them pass in their own time, neither dwelling on them, nor pushing them away you will take away the power they have over you. ‘Here you are, again, familiar thought’, you can say to yourself, ‘Or here you are again, my OCD’. No need to judge yourself, or the thought. No need to do anything special with the thought. Allow it to come into your mind, like a guest at your table, take a seat, and then leave in its own time. It may be the guest you never wanted, an uninvited guest, but just allowing it to be, and giving it no special attention, can, with practice, allow it quietly to leave of its own accord. Over time you will have a new strategy for managing OCD.

Take a moment to reflect on your thoughts or experiences trying out these strategies

Video courtesy of OCD-UK www.OCDUK.org

What else is involved in a CBT or self-help approach to OCD?

There are many elements to a full treatment of CBT for OCD. Considering the nature of your difficulties, how they have evolved over time, the meaning they have for you, and how you have tried to cope up until now are some of those elements. Another key aspect which you will find described in recommended treatments (eg NICE and SIGN Guidelines) is called ‘Exposure and Response Prevention’ or ERP.

What is ERP and how does it work?

‘Exposure’ means that in the treatment you are exposed to the anxiety you experience which is linked to your obsession. This is done in a gradual way.

‘Response Prevention’ means that you prevent yourself from dealing with your anxiety in your usual way- through your compulsions. So you prevent yourself from responding as normal, and instead let yourself feel the anxiety, and gradually learn that your anxiety will reduce over time even when you do not perform your rituals.

Depending on the nature, number and severity of your obsessions and/or compulsions, you may be successful using a self-help approach, or together with a therapist, they will tailor a unique intervention for you so that you can derive maximum benefit from treatment.

To follow a full self-help programme using an evidence-based model, we recommend you return to the list of recommended books and websites towards the beginning of this section.

If you feel you need the help of a therapist, please contact your GP in the first instance.

There is information at the bottom of this page if you require URGENT HELP

Living with…Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

If you have OCD it is likely that you spend time trying to avoid thinking about difficult thoughts that trigger your symptoms. For example you might:

- Avoid certain situations or places

- Ask other people for reassurance

- Be on the constant lookout for worrying thoughts

- Try very hard to block out certain thoughts or urges.

Although you might feel some relief from your anxiety symptoms when you engage in these behaviours, they actually make your OCD symptoms worse in the longer term. If you think back you might find that when your OCD difficulties started they were related to one or two specific thoughts or situations but over time have spread to other areas of your life.

This diagram shows how your behaviour might help in the short term but actually make things harder in the longer term. This is because acting like your worries are true makes them harder to ignore in the future.

You may be interested in reading some personal accounts of living with OCD: The following are books by two people with OCD:

The Man Who Couldn’t Stop: The Truth about OCD (2015) by David Adam

Because We are Bad: OCD and a Girl Lost in Thought (2016) by Lily Bailey

There are also detailed personal accounts at:

Find out more

Looking after someone with…Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

Information for spouses, partners and families

A recent article (Gomes et al 2014) has explored how those who live with a person with OCD can find themselves changing their behaviour to ‘work around’ the OCD. This has been called ‘family accommodation’ (FA). It includes things like providing reassurance, waiting for the person to complete their rituals, not doing or saying anything, tolerating the OCD behaviours, modifying their routine or the family’s routine, and participating in the compulsions. If the person you live with has decided they want to change, and try some self-help strategies or seek treatment, it seems to be important that those living with them also understand the principles of the treatment, for example exposure and response prevention, for the treatment to be as effective as it can be. It is important for family members to be as emotionally supportive and encouraging as they can be to someone who is trying to overcome their OCD, without helping to accommodate the obsessions or compulsions.

Therefore family members of those trying to change would do well to also familiarise themselves with the principles and aims of CBT for OCD.

There are also books written for those who live with someone with OCD:

Loving Someone with OCD: Help for You and Your Family (2014) by Karen J. Landsman

When a Family Member has OCD (2016) by Jon Hershfield

Spouses, partners and families can also find valuable information and support from the following websites:

Further information for carers is available on the NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde carers site

Real life stories

My real life experience by Sandy Nisbet

In my battle with OCD, one moment in particular stands out to me. It was a Friday night in March 2012, and I was in the study, playing a Professor Layton game. It might seem like a regular moment, but I remember it fondly. For most people, this day would have been a cause for despair. My OCD had got so severe that I had just dropped out of university. I had just had my first meeting with a psychologist. Even playing a relatively tame video game had taken a huge amount of willpower, as my OCD left very little room in my head for anything else aside from horrible thoughts and unfounded worry. But as I sat there solving puzzles, I suddenly noticed the light at the end of the tunnel, however faint. I don’t know if the tunnel had become unblocked or I had just never noticed the light before, but I caught a fleeting glimpse of it and realised, you know what? I might have a chance of beating this after all.

My OCD took a form often labelled Pure-O – obsessions without overt compulsions. I never washed hands or checked door locks excessively. In fact my OCD never had “actions” at all. Instead, my head was full of horrible thoughts that made me sick with worry. Every moral fibre in my body cried out against these thoughts, but despite this (or perhaps you could say because of this) the thoughts become more prevalent, more detailed, more abhorrent to me. Pure-O can take a few forms, but for me, involved violent thoughts – thoughts of me attacking other people. These would never leave my head, despite how much I detested them. Now when I tell my story, this is normally the part where people take a couple of steps back. But let me explain. Despite how scary these thoughts sound, these thoughts, intrusive thoughts, are thoughts that everyone has. For most people, they are shrugged off as a random misfire of the brain (and rightly so). But Pure-O sufferers react with alarm. Where did that thought come from? Does this mean something about me? Am I an evil person? Could I act on these thoughts? These questions will ring a bell to most Pure-O sufferers. And like all OCD sufferers, they will have compulsions to attempt to get rid of these thoughts. I tried to rationalise against them, and figure out where they were coming from. But attempting to stop them only led to them getting stronger, as I gave them “negative importance”. As my OCD got worse, I lost three stones in weight in three months, I was getting as little as 45 minutes sleep a night, and it got to a point where leaving the house caused a huge amount of anxiety due to the thoughts that would trigger every time I walked past someone. It was a huge issue.

My OCD began in my final year of university – I was a Computer Science student. I had stayed on to do a Masters, and there was a lot less work to do than the previous hectic Honours year. This left my brain with more time to ruminate, and all it took was one intrusive thought to set off my OCD like a match in a flour mill. My degeneration was surprisingly fast, so I quickly went to my doctor to get to the bottom of it. While not diagnosing me with OCD, he was very understanding and sent me to the community mental health unit for a more expert opinion. There, over a number of generally unhelpful meetings, I was misdiagnosed, underdiagnosed and anything in-between. At one point I specifically asked if I had OCD, but told that as I “had no compulsions”, it wasn’t OCD. I was finally diagnosed with OCD by a clinical psychologist, three months after seeking help, and was put on the waiting list for cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). It was at this point I was at my absolute lowest. I had been seeing a number of student and charity counsellors who were determined to treat me for depression, even after I got my diagnosis and explained depression wasn’t the issue. Frustrated by the waiting list and a lack of progress with the counsellors, I reached out to a private therapist. This was the turning point in my battle. She was gentle and understanding, and after a joint meeting with her and my mum, we decided dropping out of uni was the right choice. I already had a graduate job starting in four months, and my university had very graciously agreed to put forward an appeal for my degree. So I made the risky choice of leaving university, and started therapy.

While working with my therapist and the psychologist, I came to a better understanding of what these thoughts were – meaningless, and no indication of my character. Through a variety of exposure exercises designed to trigger the thoughts – such as doing DIY, gardening and cooking – I learned through practice that these thoughts led to nothing. I began to rediscover joy in the simple things, often even more that I had before. Things, such as having a meal with my family, that OCD previously sucked the happiness out of. I had lived without them for a while, but now that I could experience them again, I loved them even more.

To my surprise, the university appeal came through, and I got a distinction, alongside an award for the best Masters student! And I started my job, as a software engineer. Six years later, I haven’t looked back. I know whether this is actually possible is a cause of many heated online debates, but I believe I have fully beaten OCD. While I still have intrusive thoughts (as everyone does), I can’t remember the last time I was bothered by them.

If you are fighting OCD, I have no magical cure – CBT is the way to go. But I would give three pieces of advice. The first is this: make sure your family understand what you’re going through. Once my mum understood she was my biggest supporter. If you can’t find the words to explain it yourself, arrange for a joint meeting with a doctor or therapist. Secondly, don’t give up your hobbies. It’s easy to stop pursuing them as OCD takes over your entire being. But fight to reintroduce these things, as they give relief, and help train your brain to think normally again. And when you’re caught up in something you love, you become blissfully unaware of your OCD. Thirdly, find something that makes you laugh. It’s difficult to avoid laughing at something you find funny, even when you’re in a pit. I attribute a fair bit of my recovery to watching old episodes of The Muppet Show, or Vic and Bob. Laughter is a positive emotion that can be hard to control – the perfect counterbalance to OCD.

OCD can be beaten. A full recovery is possible, but even if not, you can still live the life you want to with the right help. Never lose sight of this. It’s easy to think things will never change if you have spent months, even years as a slave to OCD. But they do change, and you can live a happy and rewarding life. As someone at the other side of it all, I can assure you it is a life well worth fighting for.

BSL – Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

NHSGG&C BSL A-Z: Mental Health – Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) is a type of anxiety disorder. In this condition, the person suffers from obsessions and/or compulsions that affects their everyday life.

- An obsession is an unwanted and unpleasant thought, image or urge that repeatedly enters your mind, causing feelings of anxiety, disgust or unease.

- A compulsion is a repetitive behaviour or mental act that you feel you need to carry out to try to temporarily relieve the unpleasant feelings brought on by the obsessive thought.

If you have OCD these thoughts cause lots of anxiety and they can be extremely difficult to ignore. You might find that you spend lots of time worrying about what your thoughts mean. You might also complete behaviours to try and stop your feelings of anxiety.

Not everyone who experiences obsessions will have compulsive behaviours but often compulsive behaviours are very subtle and feel like a natural reaction to obsessive thoughts. You might perform a behaviour that seems unrelated to your original worry, for example repeating a certain word or phrase to yourself to “neutralise” a thought.

Some people can only suffer from obsessions, whilst others suffer from a mixture of both obsessions and compulsions.

Please note that this video is from a range of BSL videos published by NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde.